As engineering leaders, we constantly face a fundamental question of resource allocation. How do we structure our teams to maximize impact? A common dilemma is choosing between two distinct models:

- High Parallelism: Assigning single engineers per projects, creating numerous parallel work streams.

- High Focus: Creating small, dedicated teams of two or three engineers to tackle fewer, more substantial projects.

There is no single right answer, and the optimal choice often depends on your organization’s goals, maturity, and the nature of the work itself. Let’s explore the pros and cons of each approach, drawing on wisdom from known authors/books.

The Solo Engineer, Many Projects Model

This model is often tempting, especially in organizations that feel resource-constrained. It feels like you’re covering more ground by having every engineer working on something different.

Pros:

- Clear Ownership: There is no ambiguity about who is responsible for a project. That single engineer owns it, end-to-end.

- Maximized Breadth: This approach allows an organization to address a wide array of small features, bugs, and customer requests simultaneously.

- Low Communication Overhead: A solo engineer can often move faster on a small, well-defined task because they don’t need to sync with teammates, coordinate on design, or spend as much time in code reviews.

Cons:

- The “Bus Factor”: This is the most significant risk. If the solo engineer gets sick, goes on vacation, or leaves the company, the project comes to a dead halt. Knowledge is siloed, creating a critical single point of failure.

- Cognitive Overload & Context Switching: As humans, we are notoriously bad at multitasking. An engineer juggling three or four distinct projects is constantly paying the mental tax of context switching, which erodes efficiency and leads to burnout.

- Lack of Collaboration and Review: Without a teammate, there’s no one to challenge assumptions, spot potential bugs, or suggest a better design. This can lead to lower-quality code and increased technical debt.

- Blocked and Isolated: A solo engineer is more likely to get stuck waiting on a dependency from another team. They lack a teammate to brainstorm with or to help push through a blocker.

The Small Team, Fewer Projects Model

This model has become the standard for many high-performing tech organizations. It prioritizes focus and resilience over sheer parallelism.

Pros:

- Increased Velocity on Key Projects: As Will Larson notes in “An Elegant Puzzle: Systems of Engineering Management,” the goal is to staff projects to finish them, not just to start them. A team of two or three engineers can bring a significant feature to completion much faster than a single engineer ever could.

- Higher Quality and Better Design: With multiple engineers working together, you get the benefit of collaborative design, pair programming, and rigorous code review. This leads to more robust, maintainable, and well-architected solutions.

- Resilience and Shared Knowledge: The “bus factor” is mitigated. If one team member is unavailable, the project continues. Knowledge is naturally distributed among the team members.

- Mentorship and Growth: This model creates a natural environment for mentorship. Junior engineers learn from seniors, and even senior engineers learn from each other, fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

Cons:

- Higher Communication Overhead: More people working together requires more coordination. This can mean more meetings, more time spent in discussion, and a more formal planning process.

- Less Breadth: While the team is moving quickly on its primary objective, other smaller tasks and bugs may get less attention. This requires a clear process for prioritizing and triaging incoming work.

- Potential for “Too Many Cooks”: If not managed well, a small team can sometimes get bogged down in design debates or have a diffusion of responsibility. This is why keeping teams small (2-3 engineers, often called “pairs” or “trios”) is critical.

Finding the Right Balance

The consensus in modern software management, echoed in books like “An Elegant Puzzle” and also in concepts from “Team Topologies” by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais, leans heavily towards the small, focused team model for any work that is considered a strategic priority.

Will Larson argues that leadership’s primary role is to create systems that enable teams to do good work. A system that constantly pushes engineers into solo, parallel projects is often a system that prioritizes the appearance of activity over the actual delivery of impactful results. It optimizes for starting work, not for finishing it.

The solo-engineer model should be reserved for specific, limited contexts:

- Very small, isolated bug fixes.

- Highly specialized tasks where only one person has the skills (and you have a plan to train others).

- Exploratory or research-oriented work that isn’t on a critical path.

For everything else—the features that drive your business, the products that serve your customers—the focused, collaborative small team is almost always the superior choice. It delivers higher quality results faster, and it builds a more resilient and capable engineering organization in the long run.

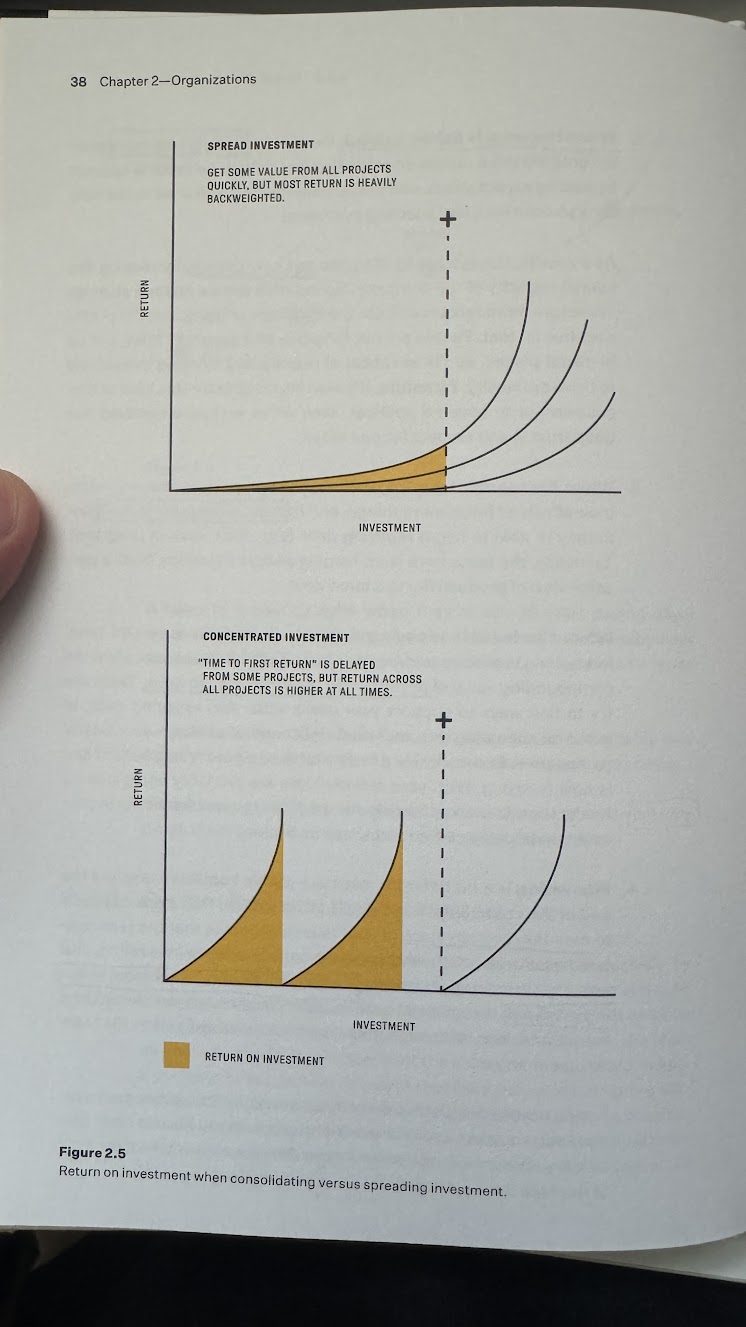

Here is an image of the book “The Elegant Puzzle” on return of investment:

Running local LLM with Ollama